The more SVV and I have fallen down the bottomless rabbit hole that is the mural world, the more we’ve learned that a lot of things aren’t so cut and dry as they appear. And even though some local advisory bodies would like to think they can regulate murals in a city, the truth is that they wouldn’t stand a chance if that case were to be taken to court. Mural law is the Wild West right now, and I’ve really loved watching artists win major cases left and right over the past couple years, some in court and others in the court of public opinion.

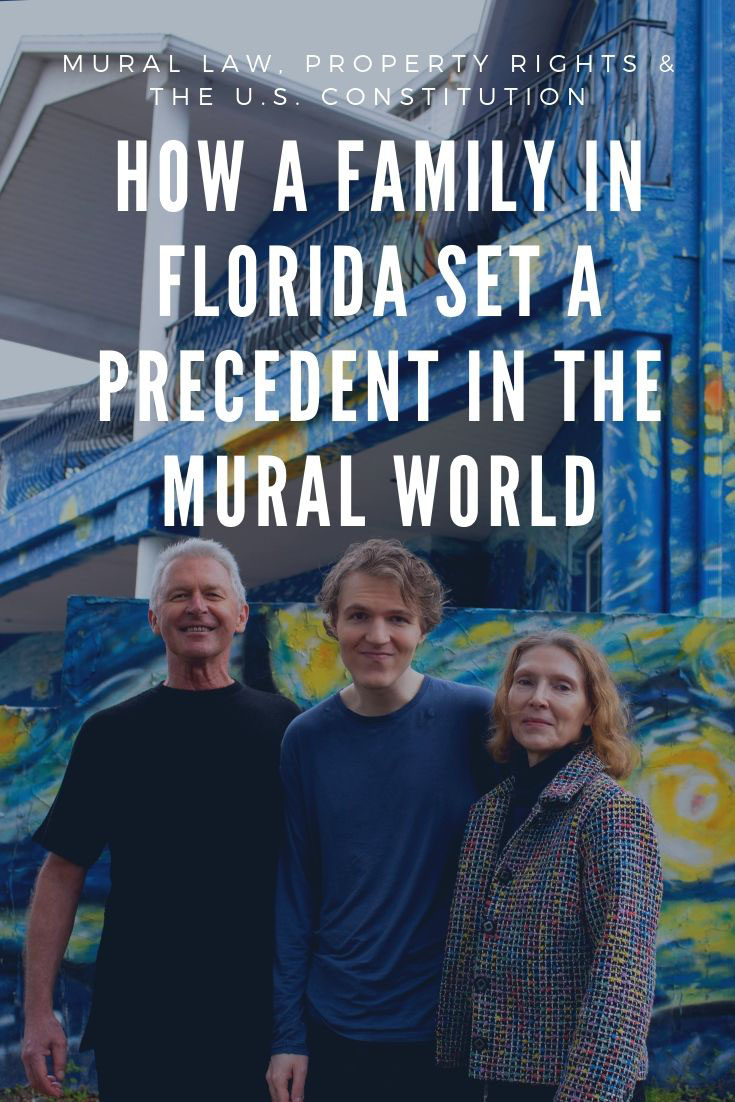

The summer before last, we watched along with the country as Pacific Legal Foundation’s Jeremy Talcott fought the city of Mount Dora, Florida—and won. Over what, you may ask? A private property owner’s right to paint the outside of their home as they chose to. That’s right, Nancy Nemhauser and Lubomir Jastrzebski opted to paint a replica of A Starry Night, the favorite piece of art of their autistic son, on a faded, yellowing wall on the exterior of their home. The city’s reaction? Fine them. The verdict?

Government must have a powerful, clearly articulated justification to regulate the exercise of First Amendment rights rather than the personal taste or whims of individual bureaucrats.

It was not only a victory in the realm of property rights, but a righteous win for artists everywhere and a warning to governments across the country that when it comes to mural law, the creator is protected both by copyright and the U.S. Constitution.

I reached out to Jeremy a year ago, and we have chatted many times since then, both on the phone and via email, about mural law, property rights and other kinds of constitutional issues pertaining to government—I used him as an expert for my full-page spread in the Sac Bee this week on how murals can make a city thrive—and he gave me permission to publish part of one of our conversations on this blog in hopes it will help shape other cities’ approach to working with artists. And hey, if you’re a muralist who is being wronged by a governmental body, Jeremy B. Talcott is the attorney you want in your corner!

How did Nemhauser v. City of Mount Dora first come about?

JBT: At first, [Nancy and Lubek] did a mural on one wall. Before the mural, it was this dowdy, white, wall stained from dirt and pollen. They knew it needed to be redone, and they had talked to this artist in town and said, “what if instead of just re-painting it, we do a mural?” They went and talked to everyone within the city, and since Mount Dora doesn’t have any aesthetic ordinances, no mural code, there was nothing prohibiting it, they went ahead and painted it.

Then the city contacted them and said: “Under our abandoned building code, we have a line where graffiti must be painted over, and we think this is graffiti and the solution for graffiti is any graffiti must be painted to match the structure on the property.” So Nancy said, “OK, well, if the house has to match the wall, we’re just going to paint the whole house.”

They went back and contracted the muralist to paint the whole house. When [Nancy] called and told me that story, I instantly thought, not only does this have a lot to do with what I care about, which is people being able to do what they want with their own property, but if she’s the type of person willing to do that, she’s the type of person willing to fight this the whole way.

Is an abandoned building code common?

JBT: Zoning ordinances and codes are so diverse across the country. It’s something that you have to research within whatever town you’re going to do something like this. You really have to look at the county codes and the city codes in the area you’re in, because there can often be layers of state and local ordinances or laws that might apply, and they might be spread across several different sections of code. While there may not be an independent “abandoned building code,” it is not uncommon for there to be some form of code enforcement regulations for abandoned, neglected, or dilapidated buildings and also for graffiti. But the fact that the graffiti regulation in Mount Dora appeared in the abandoned building code bolstered Nancy and Lubek’s case, because the mural appeared on their own occupied home.

How much power do these cities have with codes or a historic overlay? Can those be challenged?

JBT: What has pushed me into looking into this area is when we talk about what zoning codes originally were at the turn of the 20th century when what we would think of as modern-style zoning codes first came about, they were formulated to keep incompatible uses separate. The idea was that we don’t want a lot of people to build residential houses along a street and then one property owner right in the middle turns it into a factory. That was the historical idea: There’s this police power of the states and cities, which is pretty broad, so when we’re trying to protect people’s health, the cities have quite a bit of power.

But you look at what zoning codes have developed into, and it’s now this whole idea of we’re protecting a character of the neighborhood. It’s no longer about protecting people; it’s instead about wanting everything to look a certain way. Over the last 100 years, courts have upheld a lot of these kinds of regulations, and it really steps back from any sort of judicial oversight. And I think why [the Mount Dora case] initially piqued my interest is that it had this combination of not only property rights but First Amendment expression, and courts have been very protective of First Amendment expression.

If you ask my opinion, I think these cities and states have no business regulating how people’s houses look, but the fact is most of those laws have been upheld. We now have codes that are so comprehensive, that they prevent any kind of individual expression on property. We’re seeing where those two varying things are starting to clash. Now it’s starting to infringe on a core First Amendment right. Is there a way that Mount Dora could have written an ordinance that would have prevented the mural? I think so. But not under the laws that they had on the books, and it was also clear that the existing laws were being enforced unequally to punish a piece of art that was disliked. That’s where you can point to cities stepping over the line. When a city is not creating a general objective set of laws that everyone knows what’s expected of them, and instead they’re using this idea of a lot of discretion on the part of the city officials to pick and choose what they will approve and what they will not, that’s where these laws really become vulnerable.

Why do you think, ultimately, the city of Mount Dora gave in?

JBT: I think a big part of why Mount Dora settled is that they realized they did have too much discretion, and the Supreme Court has been very critical of any sort of laws that look like they’re picking and choosing based on content. If a sign code just says “all signs within the city can be no bigger than three-feet-by-five feet and they all have to be 10 feet back from any roadway,” that’s content neutral. So you don’t have to know what type of content it is to know that your sign fits into sign code.

In a lot of areas, there are still sign codes that were put together and passed before these more recent First Amendment Supreme Court decisions. There are a lot of sign codes that say “if it’s a real estate sign, it can be three-by-four feet,” “if it’s a political sign, it can only be one-by-three feet,” and “if it’s a business sign, it can be 10-by-10 feet.” If you have to see what kind of sign it is in order to know whether or not it’s prohibited, then it’s unconstitutional.

How are murals and signs treated differently in the eyes of the law when the former is art and the latter falls under advertising?

JBT: That’s kind of the interesting area of this, and at this point there hasn’t been much litigation on it. The Supreme Court has said that commercial speech deserves less protection under the First Amendment, but it’s walked back that position a bit over the last few years. A mural is clearly, generally artwork. But there are also plenty of businesses that would like to make murals, perhaps even using prominent artists, that both promote their business and have significant artistic value. And whenever you have people trying to engage in artistic expression, the First Amendment comes into play.

Even when speech is purely artistic, it doesn’t mean that government can’t restrict how people talk, paint, or express themselves, but they have to be far more careful how they do it to ensure that they don’t violate the First Amendment.

So government has to be neutral; it has to set these clear guidelines and it can’t restrict more speech than is necessary to accomplish what it’s trying to accomplish.

I think this all highlights one of the great tensions that I see right now in the way property and economic liberty are treated in the law as compared to First Amendment law involving free speech. The existing Supreme Court precedent gives local governments almost unfettered ability to impose zoning restrictions, including aesthetic zoning. But as we are seeing with these recent cases, that’s inconsistent with allowing people to engage in artistic expression on their own property. I think this intersection between speech and property is an area where there’s interesting developments to be had. More and more cities have seen the value of allowing murals. Most are hesitant to just allow free rein and not have some kind of oversight. But again, when you have government oversight of the content and the message that can be approved then that’s presumptively unconstitutional.

Similarly, economic restrictions receive very limited judicial review under the “rational basis” test. But economic activity often involves speech, and restrictions on speech are generally reviewed under “strict scrutiny.” These types of inconsistencies in the way different types of cases are treated are creating conflicts in the law that the courts are stuck trying to deal with!

So back to that question: Right now, it’s really unclear. The Supreme Court has said that cities are not allowed to look at the content of signs to determine whether or not they are permitted. But a mural can often be either: It may be purely artistic, or it may be intended to advertise a business. And what if it visually alludes to the business without more express indicators? That creates really tough questions! And I think it’s really likely that courts will be grappling with that over the next few years. There may need to be more decisions that guide courts on how to determine which of those interests dominates any particular mural. Alternatively, the Supreme Court could get rid of the commercial speech doctrine and decide that both types of speech deserve the same constitutional protection.

So, for the meantime, I think I would answer like this: Right now, there’s really no bright line test. When a mural is commissioned purely as art and does not include business names, logos, etc., I think cities will be on dangerous ground attempting to treat them as signs, even if it appears on a business wall. Where murals appear to have some sort of business or advertising motive, perhaps a city will be able to treat it as a sign. But since you have to look at the content of the mural to know which it is, that seems inconsistent with the previous Supreme Court cases! It’s likely the Supreme Court will need to take a mural case at some point and clarify the law to resolve that tension.

For cities that want to allow murals but maintain some regulatory guidelines, I would recommend passing a general mural code that governs size, location, and other objective characteristics of the mural, but does not distinguish between artistic and commercial murals, and does not require any form of pre-authorization of the content of the mural.

If you’re a building owner who wants to commission a mural, what’s the first step you’d recommend taking?

JBT: The most important first step is taking a look at the local zoning laws to see if they apply directly to murals or otherwise place restrictions on aesthetics for houses and buildings. If they don’t, go for it! In the absence of on-point regulations, you don’t need to ask government for permission to use your own property in a lawful way.

But even if there are mural codes, things are also getting more interesting right now legally: Because murals are expressive speech protected by the First Amendment, government must meet very strict legal tests when it tries to regulate murals. There have been several legal victories recently against local governments that have tried to create a “veto power” over murals, because that allows government officials to pick and choose which speech is allowed. There are still some exceptions; for example, an obscene mural would not be protected by the First Amendment. This area of the law is likely to develop further in the next few years, because some locations have very restrictive aesthetic zoning for houses that heavily restricts artistic choices on personal property, and that is in tension with the right to use your property to engage in protected speech.

And if your local government does have a review board for murals and your mural is denied, contact a public interest attorney!

For more information on starting your own mural program, read this post.

All images are courtesy of Pacific Legal Foundation, who is doing some really interesting work in the art and private property spaces. Many thanks to Jeremy for answering all my scattered questions over the course of the past year! You can contact him here if in need of legal representation.

PIN IT HERE

I’m a mural artist in Bakersfield Ca. I have done several large murals in town. I’m about to paint another large mural Honoring our two Country music icons, Merle Haggard and Buck Owens. I personally haven’t had any problems with the city about my murals, mainly because most of my murals are unveiled by the Mayor. The sign code people don’t want to mess with her. Thank you for this information! I’m sure it will come in handy someday.